When Europeans arrived in modern-day Michigan, natural resources of the North Woods helped sustain them in many ways. Guided by Anishinaabek residents, French traders and missionaries learned which native plants and animals had been utilized for centuries. Abundant fish and game, maple sugar, wild rice, nuts, berries, trees, shrubs, and other resources offered resources for every season.

Anishinaabek farmers also cultivated maize, beans, squash, and other crops for centuries before Europeans arrived on the scene. Other than dogs, however, no domesticated animals were present in modern-day Michigan prior to the turn of the 18th century. In the spring of 1706, French settlers arrived at Detroit with 10 cattle and 3 horses from Kingston, Ontario. By 1750, at least 53 farms had been established near Detroit, which included horses, cows, hogs, and poultry.

Livestock was likely introduced at the Straits of Mackinac in the 1730s. The first written account was penned by Michel Chartier de Lotbinière in October 1749. Describing a visit to Fort Michilimackinac, he wrote, “At present, in the fort, there are 3 cows and one bull, four horses one of which is a Female … about 50 to 60 hens, 7 or 8 pigs.” Elsewhere, he made note of some “fairly nice wild hay that comes up naturally but it is sparse.”

From spring through autumn, livestock foraged freely, especially eating wild plants which flourished in wet meadows and marshes. At the time, various wetland types covered over 10 million acres in Michigan, or about 17% of the present land area. Wetland ecosystems were especially prevalent along shorelines of the Great Lakes and near interior waterways. About 95% of Michigan was forested, including wooded swamps. Tallgrass prairies were common in the southwest Lower Peninsula.

To survive extreme winter conditions, horses and cattle were rounded up, penned, and fed hay and grain when the ground was snowy and frozen. Most of this forage consisted of “wild hay” until fields of “tame hay,” such as timothy grass and clover, were planted. In some areas, extensive tracts of wetland sedges and rushes covered many acres, providing many tons of livestock fodder.

As Lt. Governor Patrick Sinclair made preparations to move Fort Michilimackinac to Mackinac Island, he made special arrangements for the King’s Cattle, which provided dairy and beef for the garrison. The first cattle were sent to the island during the winter of 1780 and penned in a grassy area below Fort Mackinac. On February 15, 1780, he wrote, “…two Canadians are preparing Post & rail fence to enclose a fine grass Platt of about thirty acres for the King’s Cattle which will be sent to the Island before the Ice breaks up.” The parcel was used as pasture for more than 100 years until being transformed into a Grand Hotel golf course at the turn of the 20th century.

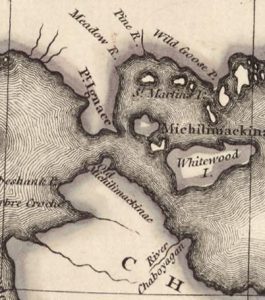

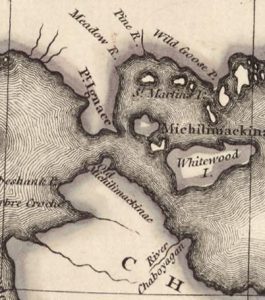

Most wild hay for the King’s Cattle was harvested on the mainland. A primary location was north of St. Ignace near the mouth of the Pine River. Known as the “Pinery,” upland portions of the site featured a large stand of pine trees used for lumber. From 1780-1783, many tons of wild hay were harvested in marshy meadows. Each July and August, plants were cut, dried, bundled, and sent to Mackinac Island on rafts towed by the sloops Welcome, Angelica, and Felicity.

Commanding the Welcome on July 23, 1781, Lt. Alexander Harrow wrote, “In the morning unloaded the vessel by the Governor’s desire took a canoe on board for the hay cutters – 6 Canadians sent on board for the raft. About 11 got under way & run to the Pinery by 1 P.M. filled the vessel with hay – in the evening brought the raft off and moored it astern.” This was one of many such journeys that summer, with hay also harvested near the mouth of the Cheboygan River.

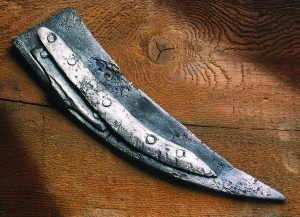

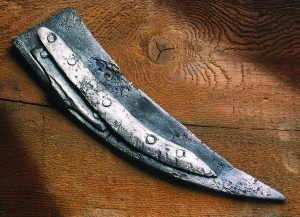

Hay was cut using common scythes, sharpened in the field with whetstones. An inventory of “Engineer’s Stores at Michilimackinac Island,” dated March 31, 1782, included 11 scythes and 4 scythe stones. Broken scythe blades, some repaired by local blacksmiths, have been unearthed archaeologically at Fort Michilimackinac, Dousman’s Mill, and the Biddle House on Mackinac Island.

As lands were cleared, seeds procured, and fields planted, cultivated hay crops such as timothy, clover, and buckwheat took precedent over wild plants. Between 1790 and 1840, Robert Campbell, John Campbell, and Michael Dousman grew about 40 acres of tame hay near Mill Creek. Dousman also operated hay farms on both Mackinac and Bois Blanc Islands, and harvested wild hay near St. Ignace. At Mill Creek, John Campbell recalled, “the meadows on this tract have always been considered very valuable, and … his father every year cut large quantities of hay upon them.” In 1830, Michael Dousman sold 30,000 pounds of “good Timothy and Clover Hay” for cattle kept by troops at Fort Mackinac.

Generally, wild hay contains about half the nutritional value of tame hay. By the 1850s, a fever for draining Michigan’s marshes quickly spread across the state. In June 1858, the Michigan Farmer noted, “In Michigan, as the winter is long, the hay crop is important, and it therefore behooves farmers to make this product as profitable as possible … The ‘tame hay,’ as it is called … is universally allowed to be the best for all kinds of stock. The ‘marsh or wild hay’ … is considered an inferior description of hay, because the grasses are not naturally as valuable for food.”

More than 240 years have passed since wooden sloops brought wild hay to the King’s Cattle on Mackinac Island. During your next visit, scan the watery horizon and imagine the scene from a bygone era. Perhaps you’ll glimpse a broad, white sail billowing in the wind. Or listen closely, and just maybe you’ll hear soft, clanking cowbells as supper makes its way across the Straits of Mackinac.