Sometimes, white-tailed deer either swim the channel or walk over ice to Mackinac Island. The island’s current small herd originates from the winter of 2014, when several deer crossed the ice from St. Ignace. In 2017, a damp deer emerged from the straits near the public library. After browsing some nearby cedars, the buck waded back into Lake Huron and swam to Round Island, about one mile away.

Historically, deer have come to the island in other unusual ways. In the early 1830s, Henry Schoolcraft “procured a young fawn” near Green Bay and brought it to his garden at the Mackinac Indian Agency, east of today’s Marquette Park. On August 17, 1835, he wrote, “This animal grew to its full size, and revealed many interesting traits… It would walk into the hall and dining-room, when the door was open, and was once observed to step up, gracefully, and take bread from the table. It perambulated the garden walks. It would, when the back gate was shut, jump over a six feet picket fence, with the ease and lightness of a bird.”

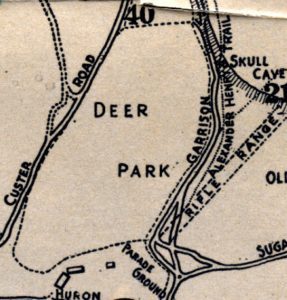

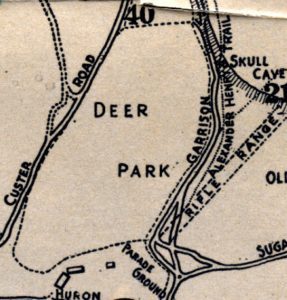

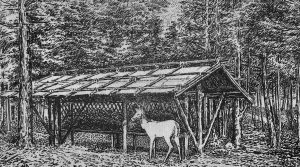

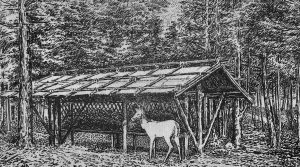

As wildlife numbers decreased through the 19th century, interest in preserving nature increased. In 1875, Mackinac National Park was created, in part to “provide against the wanton destruction of game or fish found within said park, and against their capture or destruction for any purposes of use or profit.” The Mackinac Island State Park Commission continued this mission in 1895 when Mackinac Island State Park was established. In 1901, the commission authorized a new attraction called Deer Park, north of Fort Mackinac. A tall wire fence enclosed over 10 acres, where food and shelter were provided for a herd of white-tailed deer. The herd grew substantially and was maintained for more than 40 years.

In 1910, a white-tailed deer was captured alive while swimming near Echo Island, in the Les Cheneaux area of the eastern Upper Peninsula. Caught illegally, the large buck was “promptly, and properly, confiscated by the state game warden, who removed him to the deer colony in the state park on Mackinac Island.” Author Frank Grover described the incident, expressing hope the animal would eventually die “of old age, rather than by the sportsman’s bullet.” In 1914, Park Superintendent Frank Kenyon restored the fenced enclosure, built a concrete watering basin, and cleared underbrush within Deer Park.

William Oates served as Michigan’s State Game, Fish and Forestry Warden from 1911-1917. In 1914, he noted more than 80% of the state’s primaeval forests were gone. At the time, the state’s deer population was estimated at 40,000 in the upper peninsula and only about 5,000 in the lower peninsula. Oates advocated for a “Buck Law,” limiting hunting to antlered males, which was passed in 1921. Throughout the early 20th century, it’s likely most Michigan residents never saw a wild deer in its native habitat.

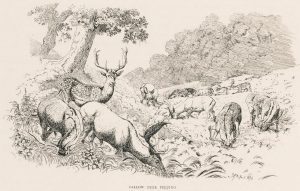

Fallow Deer on Mackinac Island

In 1913, lumber baron Rasmus Hanson donated land in Crawford County as military reserve for the national guard. Two years later, 80 of those acres were set aside as Michigan’s first State Game Refuge where deer, elk, wild turkeys, pheasants, and mallard ducks were raised. The reserve began with 25 white-tailed deer, and soon after, five European fallow deer were added. Fallow deer had been a popular attraction at the Belle Isle Zoo in Detroit since 1901. The herd sent to Grayling was originally imported from Germany to a park in Petoskey. The state game warden wrote, “The fallow deer is hardy and should adapt itself to the cover and food which Michigan affords.” He hoped to one day release them into the wild where they would “increase rapidly.” In 1917, Mackinac Island’s white-tailed herd was large enough to export 12 deer to the Hanson Refuge. In return, two of their nine fallow deer were shipped to Mackinac Island.

About 30% smaller than white-tailed deer, European fallow deer retain white spots as adults. Much variation occurs in coat color of the species, with all black and all white variants. Only bucks grow antlers, which become broad and palmate when they reach 3 years of age. To date, no photos are known of fallow deer on Mackinac Island.

Deer Park’s Demise

In 1941, The Lure Book of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, advertised Deer Park among Mackinac Island’s attractions, noting, “Back of Fort Mackinac is a natural deer park. Keep your eyes open as you drive along and you will see these shy animals back in the bush.” Not long after, however, several factors caused the site to close. During the Great Depression, a lack of visitors and reduced funding greatly affected Mackinac Island. In 1944, the state park commission decided to close Deer Park for good. During their December 5th meeting, the chairman reported “deer had been turned loose on Mackinac Island and the Superintendent was given strict instructions to use all lawful means for their protection.”

At the same time, deer were becoming common in Michigan. A decade after Deer Park opened, only about 45,000 deer roamed wild in the state. After the passage of a “Buck Law” in 1921, numbers quickly grew. In 1938, the population ranged between 800,000 and 1,000,000. By the time Deer Park closed, Michigan’s population was the largest in the United States. Today, about 2 million deer inhabit the state, and concerns of overpopulation are common.

Today, Mackinac Island visitors can still find old cedar posts and rusted wire fencing along Deer Park Trail, north of Fort Mackinac. The next time you visit the island, keep an eye out for these shy woodland residents. Although deer are common today, nothing in nature can be taken for granted. Even the commonest creatures deserve attention and care to ensure healthy ecosystems and abundant biodiversity for future generations.