Illustrated London News (Oct. 28, 1848)

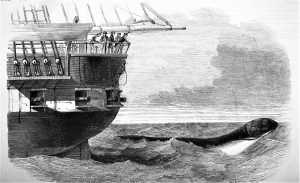

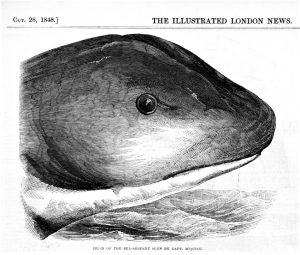

On August 6, 1848, the captain and crew of the British frigate, HMS Daedalus had a freak encounter with a “sea-serpent of extraordinary dimensions” off the west coast of Africa. When an official report reached England that October, a virtual firestorm of wild speculation, other sightings, and denouements circulated in the press for months. The Illustrated London News printed several fabulous illustrations of the beast, capturing details described by Captain Peter M’Quhae and his men. Watching the creature for twenty minutes, they estimated at least 60 feet of the creature was visible, with another 30 or 40 feet below the surface. The animal had the head of a snake, with “something like the mane of a horse, or rather a bunch of seaweed washed about its back.” Its cylindrical body measured about 16 inches in diameter, being dark brown, with yellowish-white about the throat. It had no fins, and traveled by undulating at a speed of 15 miles per hour. The British paper included examples of many additional sightings, including some of the Great American Sea-Serpent, Scoliophis Atlanticus.

American Monsters

In the United States, news of the Daedalus’ encounter spread like wildfire. While many derided the claim as fantastical, others, including Dr. Albert C. Koch, reveled in the discovery. A German-born naturalist, showman and entrepreneur, Koch first came to the U.S. in 1827, settling in St. Louis. With a flamboyant style akin to P.T. Barnum, the good doctor opened the Saint Louis Museum in 1836. Displaying both cultural and natural history specimens, exhibits included much of William Clark’s collection (of Lewis & Clark fame), acquired after his death in 1838.

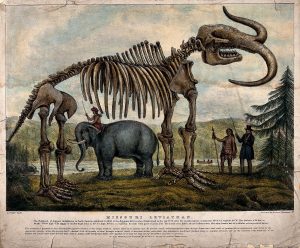

Koch’s star began to shine in 1840, when he claimed to have found the complete fossilized skeleton of the “Missouri Leviathan,” a previously unknown elephantine behemoth which dwarfed the extinct American mastodon. To increase his audience (and profits), Koch closed his museum and carted the Leviathan across the Atlantic for a European tour. The massive skeleton was particularly popular in England, where it was displayed at Egyptian Hall, in Piccadilly, London. Ultimately, Koch sold the skeleton to a British scientist before returning to America in May 1844. Only later was it discovered the Leviathan was a fabrication, composed of several mastodon skeletons, including added vertebrae and other bones to exaggerate its size.

New York City (1845)

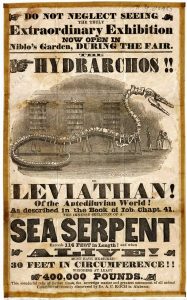

Back in the states, Dr. Koch searched for new fossilized wonders for display. In March 1845, he announced the discovery of a new monster, excavated from the rocky prairies of southern Alabama. On May 30, 1845, the Vicksburg Tri-Weekly Sentinel reported, “It is of the amphibious species, supposed to have been fiercely carnivorous, and is some thing of the alligator form except that it had fins instead of feet.” Measuring 114 feet long, Hydrarchos Harlani was displayed in New York and Boston, drawing fierce supporters and critics alike. The giant “Sea Snake” was a sensation. In 1846, Koch started another European tour, eventually selling his “specimen” to the Royal Museum in Berlin. It eventually proved to be an elaborate hoax, composed of parts from several fossilized Basilosaurus skeletons, a type of extinct whale.

The Sea Serpent at Mackinac

In June 1847, in the very midst of sea serpent mania, Horace Greeley and Lewis G. Clark boarded a steamboat at Detroit, bound for Mackinac Island. While the ship provided comfort, their Lake Huron journey was shrouded in fog and mist the entire length of the lake. Greeley, the noted editor and publisher of the New-York Tribune, was on a tour of the Great Lakes, to conclude at a Rivers and Harbors Convention in Chicago. During the pair’s brief stop at Mackinac, Greeley noted it was “among the coldest spots within the limits of our Union.”

Greeley’s companion, Lewis G. Clark, served as editor of his own publication, The Knickerbocker: or, New-York Monthly Magazine. When news of the Daedalus sighting hit the U.S. (more than a year after their Mackinac visit), Clark shared a unique perspective based on personal experience.

“Toward the twilight of a still day, near the end of July, 1847, Horace Greeley .. and ‘Old Knick’ hereof, were seated on the broad piazza of the dark-yellow ‘Mission-House’ at Michilimackinac, looking out upon the deep, deep blue waters of the Huron, when an object, apparently near the shore, suddenly attracted our attention. We both examined it through a good glass, and came to the mutual conclusion that it was an enormous sea-serpent, elevating its head, undulating its humps, and ‘floating many a rood’ upon the translucent Strait. Such was the opinion of the proprietor of the ‘Mission House,’ who in a ten years’ residence at Mackinac had never seen the like before.”

Clark delightfully describes Horace Greeley’s “tremendous kangaroo bounds” as the pair dashed for a closer look, himself getting slightly stuck in marsh mud near the shore. Reaching the beach, he continued:

“When we had arrived, lo! The object which had so excited our curiosity was nothing more than the dark side of a long undulating, unbroken wave, brought into clear relief by the level western light which the sun had left in his track as he dropped away over Lake Michigan. We felt rather ‘cheap’ as we came back together, and ‘allowed’ that if they’d seen at Nahant what we had at Mackinac, they’d have sworn that it was the sea-serpent. Catch us doing any thing o’ that kind!’”

Was Mackinac’s sea serpent nothing more than illusion, or did a mysterious creature deftly vanish beneath a convenient wave? As Lewis Clark noted, “We have been led to believe, from our own experience, that one may very easily deceived by these water reptiles.” During your next visit to Mackinac Island, keep an eye on the watery horizon. You might be surprised at what you find!