“The one thing on Mackinac Island that keeps stirring my mind is a skull … the uncouth skull of a great beast.”

Lee J. Smits (1931)

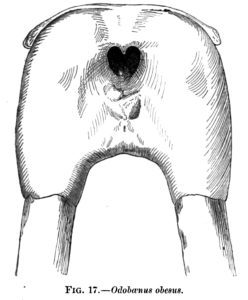

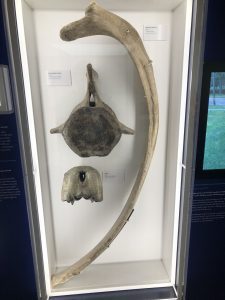

The next time you’re in Ann Arbor, be sure to stop by the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History. In the Exploring Michigan gallery, look for the oddly-shaped object shown here. On the label, you may be surprised to read: “Walrus – Recent – Mackinac Island, Michigan.” This specimen is the front portion (rostrum) of a walrus skull, with its tusks missing. Sketches from a History of North American Pinnipeds (1880) and Encyclopaedia Metropolitana (1845) are shown for comparison.

The next time you’re in Ann Arbor, be sure to stop by the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History. In the Exploring Michigan gallery, look for the oddly-shaped object shown here. On the label, you may be surprised to read: “Walrus – Recent – Mackinac Island, Michigan.” This specimen is the front portion (rostrum) of a walrus skull, with its tusks missing. Sketches from a History of North American Pinnipeds (1880) and Encyclopaedia Metropolitana (1845) are shown for comparison.

This raises several questions. When was a walrus skull discovered at Mackinac? What does “recent” mean? Did walruses once swim in Lake Huron? Read on for the amazing story of one of the most unusual objects ever unearthed at the Straits of Mackinac.

This raises several questions. When was a walrus skull discovered at Mackinac? What does “recent” mean? Did walruses once swim in Lake Huron? Read on for the amazing story of one of the most unusual objects ever unearthed at the Straits of Mackinac.

The Discovery

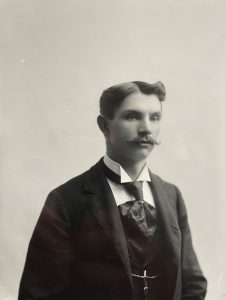

Franz (Frank) Kriesche (1863-1946) is well remembered for operating an art glass store on Mackinac Island. His shop, founded in the 1890s, offered custom glass engraving for tourists and local residents. Samples of his fine craftsmanship are on display in The Richard & Jane Manoogian Mackinac Art Museum.

On a date unremembered, Frank visited nearby Round Island, perhaps on a family picnic. Imagine his surprise when he noticed a strange lump protruding from the sand. Unearthing it did little to solve the mystery of what he discovered. At some point, the unidentified item was donated to Fort Mackinac’s first museum. Established in 1915, the exhibit was a rather haphazard collection of relics, mostly displayed in the officer’s stone quarters.

Lee J. Smits, a columnist for the Detroit Times, visited the museum in July 1931. He wrote, “the one thing on Mackinac Island that keeps stirring my mind is a skull … the uncouth skull of a great beast. Frank Kriesche found the skull on Round Island, close by Mackinac, many years ago. For a long time it was not identified. Lately there have been learned visitors who declare it is the skull of a walrus. It is not fossil, but bone. The tusks are missing. There were no other bones around the skull where it lay on the sand beach, and no one has ever come forward with the slightest clue as how it came to be there.”

Michigan’s Marine Mammals

Amazingly, this wasn’t the first marine mammal found in the state. In 1861, a whale vertebra, found in western Michigan, was noted by state geologist Alexander Winchell. In 1914, a walrus bone was unearthed at a gravel pit near Gaylord. And in the late 1920s, a sperm whale vertebra and five whale ribs were excavated at various locations throughout the state.

During the summer of 1930, Dr. Russell C. Hussey, professor of historical geology at the University of Michigan, conducted fieldwork in the Upper Peninsula. About the same time, he identified Frank’s mystery object as a walrus skull. That same year, Dr. Hussey published a report of Michigan whale bones which received national attention. His theory stated that marine creatures swam inland after the last ice age, when “the Great Lakes were once a gigantic arm of the sea,” connected by ancient river channels.

The Walrus Departs

While it had been identified, the Mackinac walrus remained at Fort Mackinac for the next two decades, unreported in scientific literature. In May 1953, Charles Handley, curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, was the first to describe the specimen. He noted that details of its discovery had turned fuzzy over time. He wrote, “R.C. Hussey… was told that the skull had been found many years ago in a beach deposit (Algonquin or Nipissing) on Mackinac Island. The original data was lost in a fire.” While Fort Mackinac’s wooden soldier’s barracks did catch fire in 1951, very little damage occurred. Perhaps the incident served as a convenient smokescreen for years of poor record keeping.

In 1954, Fort Mackinac’s collection was assessed by Alexis Proust, a curator from the Kalamazoo Public Museum. Proust spent a month on the island, “examining, sorting, and considering the potentialities of the museum.” Objects “not germane to the museum’s purpose” were to be returned to donors or disposed of. As Frank Kreische died in 1946, his walrus skull likely sat in a pile of unwanted and forgotten items. From there, it was recovered by a student and given to Dr. Hussey. In 1955, it was officially donated to the U-M museum by MSHP park superintendent Carl Nordberg.

Untangling the Riddle

In 1977, Charles Harington, curator at the National Museum of Canada, focused on a special detail of the Mackinac walrus. He wrote, “A series of nearly parallel, commonly long, cut and scratch marks are seen on the smoother parts of the cranial fragment. They are most evident on the right side of the rostrum, where a crosshatched effect is produced. I think these were produced by man … they deserve closer inspection by an archaeologist.”

Harington doubled down on his assessment in 1988, calling the skull a cultural artifact, not a natural phenomenon. He noted a similar incised pattern was evident on a walrus tusk found near Syracuse, New York. He also reported specimens from New York, Ontario, and Quebec all revealed radiocarbon dates younger than 800 B.P. (before present). As the modern Great Lakes formed about 2,000 years ago, this meant sea creatures could not have swum to Michigan, and their remains were likely transported inland by Native Americans.

After sitting in museum displays for about 80 years, the Mackinac walrus was finally subjected to radiocarbon dating. In June 1999, an expansive report, “The Late Wisconsinan and Holocene Record of Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) from North America,” was printed in the journal Arctic. Its authors noted specimens across the U.S. and Canada likely represented long-distance acquisition of walrus ivory. They wrote, “This would also seem to be the only plausible explanation of an even more remote find: the anterior part of a walrus cranium lacking tusks that was recovered from a site on Mackinac Island, Michigan, reportedly from a beach deposit, yielded an age of 975 ± 60 B.P.”

Visit the Walrus

Today, the well-traveled and sometimes mysterious Mackinac walrus remains on exhibit at the U-M Natural History Museum. The ancient skull fragment is displayed with a sperm whale vertebra and the rib of a bowhead whale, also found in Michigan. At the straits, new mysteries will be revealed during the 66th season of archaeological excavations at Mackinac State Historic Parks, which begins in June 2024. For more information, visit www.mackinacparks.com/more-info/history/archaeology