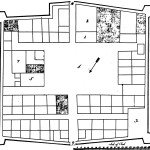

In addition to over 50 years’ worth of archaeological evidence, historians have four maps of the original community of Michilimackinac to help them understand how people lived at the fort in the 18th century. These maps, created between 1749 and 1769, provide a fascinating glimpse into the changing community of Michilimackinac.

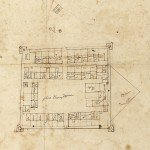

The earliest known map of Michilimackinac was drawn in October 1749 by Michel Chartier de Lotbinière, a French military engineer. Dispatched to Michilimackinac to report on the state of the post, Lotbinière recorded the fort’s defenses (which he considered “very badly built”) as well as the layout of the community within the walls. His map also listed the residents of most of the fort’s 40 homes, as well as the few buildings occupied by the French military and the Catholic priest. In an accompanying written report, Lotbinière also provided a number of details about the construction and design of the built environment at Michilimackinac.

The earliest known map of Michilimackinac was drawn in October 1749 by Michel Chartier de Lotbinière, a French military engineer. Dispatched to Michilimackinac to report on the state of the post, Lotbinière recorded the fort’s defenses (which he considered “very badly built”) as well as the layout of the community within the walls. His map also listed the residents of most of the fort’s 40 homes, as well as the few buildings occupied by the French military and the Catholic priest. In an accompanying written report, Lotbinière also provided a number of details about the construction and design of the built environment at Michilimackinac.

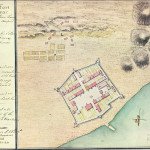

Lt. Perkins Magra of the British 17th Regiment created the next map of Michilimackinac in 1765. After Capt. William Howard requested improvements at Michilimackinac, the British realized they had no maps of the post, so the duty fell to Magra. Magra was particularly interested in depicting the living quarters available to the British army, and so his map recorded the inhabitants of the fort’s buildings using a combination of colors and letters. Magra carefully noted which houses were inhabited by British officers, soldiers, and merchants, while homes of French-Canadian families were left unmarked. Magra’s map was also the first to depict the final configuration of Michilimackinac, which had been enlarged by the French sometime in the 1750s.

Lt. Perkins Magra of the British 17th Regiment created the next map of Michilimackinac in 1765. After Capt. William Howard requested improvements at Michilimackinac, the British realized they had no maps of the post, so the duty fell to Magra. Magra was particularly interested in depicting the living quarters available to the British army, and so his map recorded the inhabitants of the fort’s buildings using a combination of colors and letters. Magra carefully noted which houses were inhabited by British officers, soldiers, and merchants, while homes of French-Canadian families were left unmarked. Magra’s map was also the first to depict the final configuration of Michilimackinac, which had been enlarged by the French sometime in the 1750s.

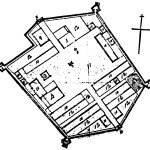

The next map of Michilimackinac was drawn soon after Magra produced his colorful depiction of the post. This map is perhaps the most mysterious of the four Michilimackinac maps, as its delineator, date of creation, and even its purpose remain unknown. Not as detailed as Magra’s map, it nonetheless depicts the various government properties scattered throughout the fort. Minor differences from Magra’s map, combined with archaeological evidence, suggest that the drawing was created sometime between 1766 and 1769.

The next map of Michilimackinac was drawn soon after Magra produced his colorful depiction of the post. This map is perhaps the most mysterious of the four Michilimackinac maps, as its delineator, date of creation, and even its purpose remain unknown. Not as detailed as Magra’s map, it nonetheless depicts the various government properties scattered throughout the fort. Minor differences from Magra’s map, combined with archaeological evidence, suggest that the drawing was created sometime between 1766 and 1769.

The final Michilimackinac map was drawn in June 1769 by Lt. John Nordberg of the 60th Regiment. Since at least 1765, Commander in Chief Thomas Gage had dealt with numerous pleas for a barracks to be built at Michilimackinac (as noted on Magra’s map, British soldiers, like French troops before them, lived in rented homes). When Gage finally authorized barracks for Michilimackinac, Capt. Beamsley Glazier complained that “the King has no ground in the Fort” upon which to build the new structure. Realizing he had misspoken (the British actually owned several plots, including the large parade ground in the center of the fort), Glazier ordered Nordberg to prepare a map for Gage. Nordberg’s map dutifully recorded all British government property, including the parade ground where barracks were built later that year.

The final Michilimackinac map was drawn in June 1769 by Lt. John Nordberg of the 60th Regiment. Since at least 1765, Commander in Chief Thomas Gage had dealt with numerous pleas for a barracks to be built at Michilimackinac (as noted on Magra’s map, British soldiers, like French troops before them, lived in rented homes). When Gage finally authorized barracks for Michilimackinac, Capt. Beamsley Glazier complained that “the King has no ground in the Fort” upon which to build the new structure. Realizing he had misspoken (the British actually owned several plots, including the large parade ground in the center of the fort), Glazier ordered Nordberg to prepare a map for Gage. Nordberg’s map dutifully recorded all British government property, including the parade ground where barracks were built later that year.

These four maps, created over a 20 year period, reveal a great deal about the French and British inhabitants of Michilimackinac, depicting where individual families lived and demonstrating how the fort changed over time.