Although the light at the top of the tower may be the defining feature of most lighthouses, stations like Old Mackinac Point usually had another, equally valuable signaling system to help keep sailors safe. The light, while valuable in relatively clear conditions, couldn’t always be seen through haze, smoke, driving rain, or fog. During times of low visibility, the keepers turned on Old Mackinac Point’s other signaling system: the fog whistle.

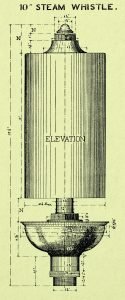

All whistles work by blowing a gas across an orifice, or opening, into a resonating chamber called a bell. The edge of the bell creates turbulence as the stream of gas is split in two, with some gas entering the bell while the rest passes through the orifice and out into the surrounding air. The turbulent gas inside the bell bounces around, alternately compressing (making more dense) and rarefying (making less dense) the air inside. These compressions and rarefactions create vibrations in the bell, which we perceive as sound. The frequency of these vibrations, which translate to the whistle’s pitch, depends, among other things, on the overall length of the bell- longer bells produce lower frequencies, which we hear as deeper pitches. Deeply-pitched sounds can be heard at long distances, making them ideal for fog signals.

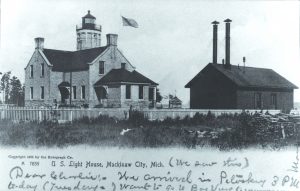

A fog whistle was actually the first thing built at Old Mackinac Point, going into operation in 1890, two years before the lighthouse itself was completed. The original fog whistle consisted of a corrugated metal building housing two locomotive-style steam boilers. Two 10-inch diameter steam whistles were mounted above the roof. Only one whistle and boiler were used at a time, with the other maintained as a redundant backup system. In 1906 the Lighthouse Service replaced the original fog whistle building with a new brick structure housing the old machinery. The old corrugated metal building was relocated and served as a warehouse until torn down in the 1940s. The new fog signal retained the double boilers, but featured only a single 10-inch whistle mounted on the north wall, facing the Straits of Mackinac.

Regardless of how they were housed, Old Mackinac Point’s fog whistles worked in the same manner. To sound the whistle, keepers first had to build up steam in the boiler. Station logs indicate that the keepers burned both wood and coal, depending on what was available from local vendors. Once they had built up a head of steam, they started a small timing mechanism that regulated the flow of steam to the whistle. This mechanism automatically sounded Old Mackinac Point’s distinctive fog signal signature: 5 seconds of sound, 17 seconds of silence, 5 seconds of sound, 33 seconds of silence.

Once the steam passed through the automatic valve, it traveled from a 2¼-inch pipe into the foot of the whistle, which directed it upward across the orifice and towards the bell. The size of the orifice (the distance between the foot and the bell) could be altered to create different tones. The steam that passed into the bell entered an 18-inch tall resonating chamber, where it expanded and vibrated to create a deep bass tone audible for several miles.

Old Mackinac Point retained its steam whistles until 1933, when they were replaced by air horns running on compressed air. Today, a new whistle has been installed on the 1906 fog signal building, and historical interpreters sound it for demonstrations every day. A brand new exhibit inside the keepers’ quarters, meanwhile, examines how the science of sound and light were harnessed as signaling devices at Old Mackinac Point. We hope you’ll join us at the lighthouse this fall and hear the whistle in action!