“The best potatoes in the world grow at Mackinac.” – Army and Navy Chronicle, September 1835

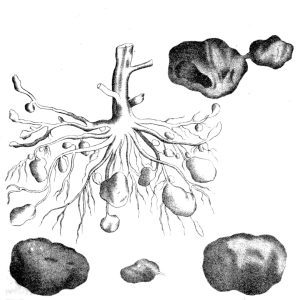

Most people easily recognize two kinds of potatoes. A sweet potato has orange flesh and belongs to the morning glory family. Distantly related, the common potato is large and white-fleshed, being part of the nightshade family. The latter type was domesticated by Native Americans in South America at least 7,000 years ago. Introduced to Europe by the late 16th century, it eventually became a dominant crop, especially in Ireland. Potato plants flourish in a variety of soils, providing more calories per acre than grain. Today, more than 5,000 different varieties are grown across the globe.

Common potatoes weren’t grown in North America until the early 18th century. Brought to New England from Ireland, this variety became known as the “Irish potato.” Potatoes were first planted at the Straits of Mackinac by the British. John Askin grew them near Fort Michilimackinac in the 1770s, keeping meticulous records. As the garrison relocated to Mackinac Island, large gardens were planted below the new fort, near the harbor. When Americans arrived in September 1796, they found a commandant’s garden “filled with vegetables” and an adjacent plot “filled with potatoes.” A government garden provided fresh produce for soldiers for more than 100 years before being transformed into Marquette Park.

Gardeners at Mackinac discovered these hardy tubers needed little soil to thrive there. In 1820, Henry Schoolcraft noted, “Potatoes have been known to be raised in pure beds of small limestone pebbles, where the seed potatoes have been merely covered in a slight way, to shield them from the sun, until they had taken root.” By this time, several small farms dotted the island where potatoes were a staple crop.

Rev. William Ferry operated a Protestant mission on Mackinac Island from 1823–1834. The Mackinaw Mission operated a school and boarding house for Anishinaabek children. Located near the southeast shore, staff and pupils maintained a five-acre garden stocked with potatoes, peas, beans, and other vegetables. In 1826, the mission also purchased the John Dousman farm, along the western shore. There, they grew 10 acres of potatoes and other crops.

As tourism grew, the reputation of Mackinac potatoes (usually spelled Mackinaw) spread far and wide. In 1835, visitors found a potato patch near Fort Holmes, writing, “There are about eight or ten acres on this summit cleared up, part of them being enclosed as a potato field. The best potatoes in the world grow at Mackinac, and this plat of them looked very flourishing.” They were amazed, observing plants “flourishing among pebbles where there is no more earth than in a stone wall. The Mackinackians do not regard earth as necessary in a garden, and perhaps would dispense with it even in a farm.”

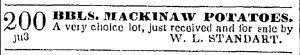

As tourists departed, some carried seed potatoes to plant at home. In 1837, Solon Robinson experimented with several northern crops in Iowa, including an early variety named Mackinaw blue. By the 1840s, some voiced the opinion that Mackinac Island potatoes rivaled those grown in Ireland. Extolling virtues of the straits, Dr. Daniel Drake wrote, “the potatoes of this region, rivalling those of the banks of the Shannon, and the white-fish and speckled trout of the surrounding waters … render all foreign delicacies almost superfluous.” On July 31, 1847, a correspondent for the Detroit Free Press boldly stated, “The fine potatoes raised on the island are irresistible –all passengers want them, and sailors will have them.” For decades, the Mackinaw potato enjoyed a celebrated status, renowned across the nation.

What made Mackinaw potatoes so special? They grew large, ripened early, and were celebrated for their “mealiness.” A mealy potato is dry, fluffy, high in starch, and low in sugar. These traits make them excellent for baking, mashing, or serving deep fried. The plants themselves were also resistant to potato rot, a disease which decimated crops in Ireland, resulting in widespread famine between 1845-1852. Many Irish immigrant families settled at Mackinac during this period, some fleeing desperate conditions in their homeland.

By the late 1840s, potato blight had also affected crops in the United States. Disease reduced production by more than one-half, while doubling the price per bushel. Blight resistant varieties, including the Mackinaw, were highly sought after. In 1852, Samuel H. Addington displayed Mackinaw White potatoes at the New York State Fair. Two years later, a report for the U.S. Patent Office noted, “Most of the fine varieties formerly cultivated … have been abandoned, and those less liable to disease substituted, such as the Boston Red, the Carter, and the Mackinaw.”

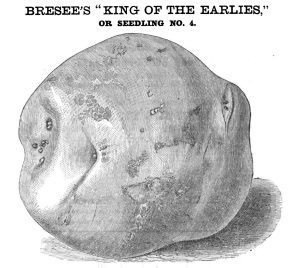

At the same time, hundreds of new varieties were being developed. Fueled by a robust profit motive, “Potato Mania” gripped the farming community. In 1869, George Best wrote, “during the past two years the most intense excitement has prevailed in regard to the Potato, and fabulous prices have been paid for seed of new varieties, which, it was hoped, would more than take the place of old kinds.” An extreme example, King of the Earlies sold in 1868 at the price of $50.00 for a single potato. With such advancements, old varieties, including the Mackinaw, eventually fell out favor. By the 1920s, it had virtually disappeared from the market.

In January 2022, researchers at Michigan State University unveiled several new potato hybrids. One of the most promising lines was named the Mackinaw (MSX540-4). A cross between “Saginaw Chipper” and “Lamoka,” it stores well, and it is highly resistant to several diseases. This attractive variety also performed highly in the Potatoes USA National Chip Processing Trials. With any luck, the new Mackinaw potato may even find its way to your next game-day celebration.