“To converse, as it were, with nature, to admire the wisdom and beauty of creation,

has ever been, and I hope ever will be, to me a favourite pursuit.”

Thomas Nuttall (1821)

On August 12, 1810, Thomas Nuttall stepped ashore on Mackinac Island, becoming the first trained botanist to explore northern Michigan. A native of Yorkshire, England, Nuttall arrived in America in 1808, intent on learning as much as possible about living things in the New World, whether they had leaves, petals, scales, fur, or feathers. Like many of his European counterparts, Nuttall was interested in Native American culture, North American geology, and the continent’s winding waterways. His wide-ranging travels led him from gardens of America’s leading scientists, through the Great Lakes, along the continent’s greatest rivers, over mountains, and all the way to California, Hawaii, and South America.

This extraordinary explorer kept journals of his adventures (unfortunately omitting his journey from Detroit to Green Bay), and published several books which detailed his scientific discoveries. At Detroit, he recorded the start of his journey to Mackinac, writing, “On July 29th, I left Detroit for Michilimakinak in a birch bark canoe accompanied by the surveyor of the territory.” The surveyor was Aaron Greeley, headed to measure private land claims at the straits, including those of John Campbell at Mill Creek, and Michael Dousman on Mackinac Island.

Nuttall botanized at the Straits for several days before hitching a ride with a group of traders bound for John Jacob Astor’s ill-fated fur trading post, Astoria, located in modern-day Oregon. In his book Astoria, author Washington Irving described the enthusiastic 25-year-old botanist as he appeared in March 1811, while his group ascended the Missouri river. Depicted just seven months after leaving Mackinac Island, one can easily imagine Nuttall shared similar experiences with Aaron Greeley along the Lake Huron coastline.

“Mr. Nuttall seems to have been exclusively devoted to his scientific pursuits. He was a zealous botanist, and all his enthusiasm was awakened at beholding a new world… Whenever the boats landed at meal times, or for any temporary purpose, he would spring on shore and set out on a hunt for new specimens. Every plant or flower of a rare or unknown species was eagerly seized as a prize. Delighted with the treasures spreading themselves out before him, he went groping and stumbling along among a wilderness of sweets, forgetful of every thing but his immediate pursuit, and had often to be sought after when the boats were about to resume their course.”

Nuttall retreated to England to avoid the War of 1812, then returned to Philadelphia in 1815. After three years collecting more specimens and organizing his collections, he published, The Genera of North American Plants, and a Catalogue of the Species, to the Year 1817. This important two-volume work included 60 species of plants from the Great Lakes region, about a third of which were new to science. Those from the Straits of Mackinac included thimbleberry, dwarf lake iris, twinflower, beach pea, and birdseye primrose.

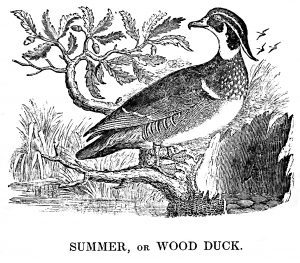

In March 1823, Thomas Nuttall accepted a position as Curator of the Botanic Garden at Cambridge, Massachusetts. Over the course of his residence, he was encouraged to write about birds, which he had studied since his arrival in America. The result was A Manual of the Ornithology of the United States and Canada. Published in two volumes, The Land Birds (1832) and The Water Birds (1834) were affordable and popular, featuring simple woodcut illustrations, which the author lamented were “not sufficiently numerous, in consequence of their cost.” In 1832, Ralph Waldo Emerson recommended the work to a friend, writing, “there is a beautiful book on American birds by Mr. Nuttall that every one who lives in the country ought to read.”

The intrepid botanist endured numerous collecting trips over the next decade, often at severe cost to his personal health and safety, as he crisscrossed North America and beyond. In 1841, he sailed back to England to live on an estate, “Nutgrove,” inherited from his uncle. There, he spent the last 17 years of his life before succumbing to illness on September 10, 1859, at the age of 73.

The complete accomplishments of Thomas Nuttall greatly eclipse his brief visit to the Straits of Mackinac in 1810. More than 200 years later, perhaps the most lasting legacy of this humble, hard-working botanist is his self-described “fervid curiosity” and intense love of nature which continues to inspire curious wanderers in the 21st century.