“There are more cows in Mackina than in any other place of its size in the known world; and every cow wears at least one bell.”

Much has been written about the Battle of Mackinac Island, which took place between American and British forces on July 18, 1814. Often disregarded, however, are bovine witnesses to the melee which occurred that summer’s day on pasture and woodlots of Michael Dousman’s farm. This is their story.

The King’s Cattle

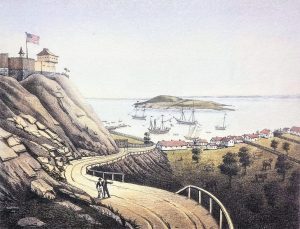

During the autumn of 1779, Lieutenant Governor Patrick Sinclair began transferring the British garrison at Fort Michilimackinac to Mackinac Island. At the time, local residents included the “King’s Cattle,” kept for providing fresh beef and dairy products. Construction on the island began that winter, with cattle driven over the frozen straits before spring. On February 15, 1780, Sinclair wrote, “…two Canadians are preparing Post & rail fence to enclose a fine grass Platt of about thirty acres for the King’s Cattle which will be sent to the Island before the Ice breaks up.”

This “fine grass Platt” is a rolling plot of land, west of and below Fort Mackinac. For well over a century, it was known as the government (or public) pasture. In 1901, the Mackinac Island State Park commission leased the parcel to the Grand Hotel for use as a 9-hole golf course.

In addition to provender, trained cattle served as working oxen. On July 30, 1780, Sinclair complained to his superiors, “… endeavors to secure this Garrison have been retarded for want of working Cattle, Tools, the materials and Rum.” That November, two cows were added to the island’s herd, transported from the mainland aboard the armed sloop, HMS Welcome.

Dousman’s Farm

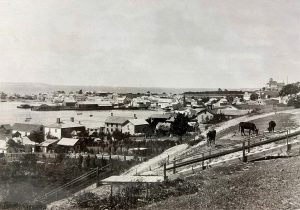

American troops took control of Fort Mackinac in 1796. Civilian arrivals included Michael Dousman, who established a large farm on the northeast corner of the island. On July 17, 1812, British troops conscripted Dousman’s oxen to haul their cannon across the island, leading to an American surrender. In 1814, those same oxen presumably bore witness to the bloody battle between American and British forces, which took place on Dousman’s hay fields.

Michael Dousman filled island contracts for fresh beef, hay, lumber, and firewood for nearly 50 years. Several accounts noted his herd numbered about 20 head of cattle. In 1852, Juliette Starr Dana stopped for a visit, writing, “… we came to a large farm with oxen, outbuildings & everything in New England Style. We went to the house & asked permission to rest, which was which was granted very kindly by the woman of the house who handed each of us a large bowl of rich milk cold as ice, which proved very refreshing.” In 1856, Michael Early bought the property and continued maintaining a dairy farm.

Mackinac’s Meandering Cattle

Photo by Lieut. Benjamin C. Morse Jr. (1890)

Other local residents also owned cattle, which often roamed at will, grazing as they pleased. In September 1835, Chandler R. Gilman spent a rustic night in a local boarding house. “This morning I waked very early,” he wrote. “At dawn heard the morning gun from the Fort, and soon after a clattering about the house; and the noise of cow-bells under the windows gave us notice that the world was astir … There are more cows in Mackina than in any other place of its size in the known world; and every cow wears at least one bell.”

Wandering cows posed challenges for decades. Once Mackinac National Park was created in 1875, a new law barred cattle from running loose at night. Two years later, Captain Joseph Bush posted a notice that all stray cows would be put in a pound until reclaimed by their owners. Like most early park regulations, these proved difficult to enforce.

A turnstile was installed at the bottom of Fort Mackinac’s south sally ramp to deter four-legged visitors from sauntering to the top. Fanny Dunbar Corbusier, wife of the post surgeon, arrived in April 1882. She recalled, “People on foot usually climbed the long flight of steps that were the shortest way up to the [officers’] quarters, and a cow once chose this route, climbing until she reached the parade ground, some one hundred and twenty steps up.”

The Cow-Bell Nuisance

Free-ranging cattle failed to amuse Illinois congressman, William Springer. His family spent the summer of 1884 on the island, contemplating leasing a lot and building a cottage. The following spring, he informed Captain George K. Brady they had decided to spend summers elsewhere. He wrote, “Owing to the ‘cowbell nuisance’ Mrs. Springer did not get the rest desired … and as a result has been in ill health the entire winter.”

Arthur Fisk Starr, on the other hand, delighted in the noisy situation. From 1883-1890, the “merry charioteer” ran the most celebrated carriage service of the national park era. Starr’s Chariot led tours across the island, full of “fun, philosophy, and unwritten history.” After stopping at Lover’s Leap, a guest wrote, “No drive could be more beautiful. A pause was made at a point where several roads meet. This is Cow-Bell Point. The drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds … It is said that at Cow-Bell Point the bells can be heard no matter on what part of the island the cows are.”

Likely, you won’t encounter a single cow on your next Mackinac Island visit. As you wander, imagine a time when lowing “moos” and tinkling cowbells were defining features of the Wonderful Isle. Listen closely, and you just might catch faint echoes from this bygone era.