On November 22, 1822, the Detroit Gazette reprinted a remarkable tale which captivated readers across the country. Originating in New Orleans, the account first appeared in the Louisiana Advertiser that September. The story was eventually printed by dozens of newspapers in at least 16 states, and the nation’s capital. It was a story which began eight years earlier, during the Battle of Mackinac Island.

A short version from the Nov. 13, 1822 edition of the Gettysburg Compiler reads, “Something Extraordinary. On the 15th of August at New Orleans, a musket ball was extracted from the body of Mr. J. Wingard, where it had remained since the 4th of August, 1814; when it was received at the battle of Mackinac, under Col. Croghan. When extricated, the part flattened by the bone was covered with a black crust, which on being dried and set fire to, exploded with a white flame similar to fresh powder, with the exception of a sulphurous [sic.] smell, from which it was entirely free.”

Reading this improbable tale raises many questions. Who was J. Wingard? Did he really carry a musket ball (and powder) in his body for 8 years, from Mackinac Island to New Orleans? How did it happen, and what happened to him? A closer look provides some answers to this forgotten soldier’s sacrifice.

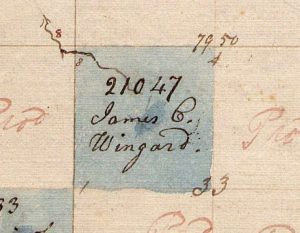

Sergeant James C. Wingard

British forces captured Fort Mackinac during a surprise attack on July 17, 1812. More losses followed, including the surrender of Detroit in August. In January 1813, the Battle of the River Raisin, near Monroe, Michigan, resulted in a bloody and decisive British victory. The stinging defeat decimated the Kentucky Volunteer Militia and 17th U.S. Infantry. The battle gave rise to the cry, “Remember the Raisin!”

When the news reached Kentucky, 4,000 proud Kentuckians volunteered to fight. On May 11, 1813, James C. Wingard joined the 1st Company of the 17th Regiment of U.S. Infantry as a sergeant. Upon enlistment, he was 34 years old and employed as a carpenter. Born in Maryland about 1779, Mr. Wingard stood 5’11’’ tall, with gray eyes, dark hair, and a fair complexion.

Aided by fresh Kentucky forces, Americans recorded victories in late 1813, including the recapture of Detroit. The following summer, they were ready to retake Mackinac. A letter from Detroit, written July 3, 1814, reads, “The expedition against Mackinaw will set out the first fair wind up the river; the whole commanded by the brave colonel G. Croghan and major Holmes. Their command will consist of about seven hundred men…They calculate on serious business, before we get possession of the place.”

Delayed by a headwind, all five American gunships finally entered Lake Huron by July 13. To meet them, Sergeant Wingard led his company with other foot soldiers from Detroit to Fort Gratiot, at Port Huron. An expedition member wrote, “The land forces arrived here yesterday, having marched by land fifteen miles through a very ugly and wet country without even a path the greater part of the way.” After troops boarded the ships, the flotilla embarked on its fateful journey north.

The Battle of Mackinac Island

American forces, commanded by Lieut. Colonel George Croghan, landed near the north shore of Mackinac Island on August 4, 1814. The battle which ensued lasted little more than an hour, but cost the Americans 75 casualties, including 13 killed and seven who later died of wounds. Injured men, along with the body of fallen Major Andrew Hunter Holmes, crowded on the U.S. Sloop of War, Niagara. On August 11, they set sail toward Detroit, including Sergeant Wingard, who carried a British musket ball lodged in his pelvis.

American forces, commanded by Lieut. Colonel George Croghan, landed near the north shore of Mackinac Island on August 4, 1814. The battle which ensued lasted little more than an hour, but cost the Americans 75 casualties, including 13 killed and seven who later died of wounds. Injured men, along with the body of fallen Major Andrew Hunter Holmes, crowded on the U.S. Sloop of War, Niagara. On August 11, they set sail toward Detroit, including Sergeant Wingard, who carried a British musket ball lodged in his pelvis.

After the War

Despite serious injury, Wingard remained enlisted in the service. In October 1814, he received a furlough (leave of absence) in Cincinnati, Ohio. Records indicate he was “debilitated by a wound” at the time. Sergeant James Wingard received his discharge from military at Newport, Kentucky on May 6, 1815. Thereafter, he settled in Hamilton County, Ohio, with his wife, Elizabeth.

After the war, Mr. Wingard received an invalid pension, authorized by the U.S. Congress for wounded veterans. Initially, pensions were granted to injured commissioned and non-commissioned officers and to heirs of soldiers who died during the war. On April 16, 1816, Wingard was placed on the pension roll with an annual allowance of $30. He later received two increases, eventually earning $96 per year for his injury sustained on Mackinac Island.

Congress also authorized land grants for War of 1812 veterans. At first, military bounty lands were limited to districts in Arkansas, Illinois, or Missouri. On March 27, 1819, Wingard applied for a 160-acre tract in northern Arkansas Territory. His claim was granted January 28, 1822.

A Beautiful White Blaze

On August 15, 1822, James Wingard was placed on a surgeon’s table in New Orleans, Louisiana. Over the years, previous attempts failed to extract the lead lodged in his pelvic bone. When it was finally removed, doctors noticed a mysterious dark crust on its flattened surface. Being dried, the substance was scraped onto a glass plate. The longer story concludes, “a part of which…was put on a strip of white paper, the end of which was set on fire, and no sooner had the fire come in contact with the supposed powder than it exploded with a beautiful white blaze, much to the consternation of all the gentlemen present: a second trial was made with equal success.” The story fails to mention that Mr. Wingard died that day, at 43 years of age. His pension record simply notes, “Died the 15th August 1822. Original Certificate of Pension surrendered.”

Two hundred years ago, the incredible tale of Sergeant James Wingard, a survivor of Mackinac Island’s most terrible day, was the talk at dinner tables across the nation. As families gather this Thanksgiving, may we give thanks for all veterans, even those whose stories are forgotten. Their collective courage and sacrifice provide freedoms we now enjoy, and all too often take for granted.