“It is reported that wild pigeons have arrived in this section, and are coming in great numbers. This would, we think, indicate that winter was over.”

Northern Tribune, March 9, 1878

Cheboygan, Michigan

As long as people have lived in the north woods, they’ve eagerly awaited signs of spring. For many centuries, the season of melting ice and flowing maple sap was also marked by tremendous flocks of passenger pigeons arriving from the south. For the past 130 years, however, no one has experienced the awe of a pigeon flock descending like a force of nature. Ectopistes migratorius, the passenger pigeon, has disappeared.

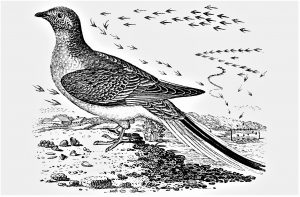

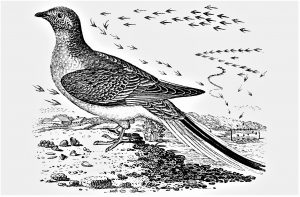

While related to pigeons and doves of today, passenger (or wild) pigeons were unique in the animal kingdom. About 50% larger than a mourning dove, the species was known for its long tail and wing feathers, bright iridescent plumage, and deep red eyes. Congregating in huge flocks, they flew at speeds up to 60mph and settled in colonial nesting sites covering many thousands of acres. These colorful birds were common east of the Rocky Mountains, especially where their favorite foods of acorns and beech nuts were abundant.

At the Straits of Mackinac, archaeologists have found passenger pigeon bones at Colonial Michilimackinac and Dousman’s Mill, especially near Native American and French-Canadian habitations. Describing the Straits in 1773, trader Peter Pond noted “These Wood afford Partreages, hairs, Venesen, foxis & Rackcones, Sum Wild Pigins.”

Arriving in flocks of millions, pigeons meant a suddenly abundant food source during a lean time of year. Thomas Nuttall, the first botanist to explore the Straits, also studied birds. In 1832, he wrote: “The approach of the mighty feathered army with a loud rushing roar, and a stirring breeze, attended by a sudden darkness, might be mistaken for a fearful tornado about to overwhelm the face of nature. For several hours together the vast host, extending some miles in breadth, still continues to pass in flocks without diminution… and they shut out the light as if it were an eclipse.”

In the 19th century, accounts of pigeons at the Straits became increasingly common. In July 1852, Lyster O’Brien, 15-year-old son of post chaplain Rev. John O’Brien, wrote from Fort Mackinac: “My dear Uncle, We are all happy to learn that you are coming here, and will you please bring up your gun with you, for we expect plenty of pigeons this summer, and I think we can tramp all over the Island with you after them…”

Pigeons not eaten locally were killed by market hunters who travelled far to find roosting flocks. After being packed in barrels of salt for preservation, their harvest was shipped to cities such as Detroit, Chicago, and New York, where hotels and restaurants bought them by the dozen. Crates of live pigeons were sold for trapshooting competitions.

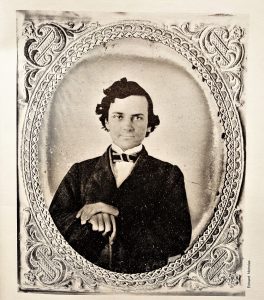

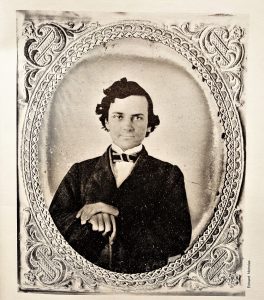

In 1862, Henry T. Philips opened a grocery business in Cheboygan. He quickly became a major exporter of wild game, shipped by steamboat and railroad. He recalled, “In 1864… I had a shipment of live wild pigeons which we brought down the Cheboygan River from Black Lake in crates holding six dozen each… In 1868, at Cheboygan, I took over six hundred fat birds at sunrise. I sold to the United States officers at Mackinac for trap shooting, also to Island House [hotel].”

Organized by groups such as the Cheboygan Gun Club, trapshooting matches were popular from the 1850s through the 1890s. On July 4, 1880, a target shooting match pitted members of the Cheboygan club against Fort Mackinac soldiers. After the contest, some races were held, followed by a public “pigeon shoot” featuring 15 dozen birds.

In 1878, the largest colonial nesting in Michigan history occurred near Petoskey, covering an area of 150,000 acres. The following year, in his Annotated List of the Birds of Michigan, Dr. Morris Gibbs noted wild pigeons were “exceedingly common some seasons.” In such huge numbers, it seemed unimaginable their population would ever decline.

Market hunting, trap shooting, and extreme habitat loss due to lumbering caused pigeon numbers to fall sharply through the 1880s. The last large nesting in Michigan occurred in the spring of 1881, near Traverse City. That same year, a heavy sleet storm occurred on October 15 as a large flock of pigeons flew south across the Straits of Mackinac, causing many to drop into the water and drown.

On April 22, 1882, Cheboygan’s Northern Tribune reported: “Some of our hunters were led to believe there were pigeons in plenty a few miles from town… but it was only a cruel hoax.” A few years later, Morris Gibbs observed pigeons on Mackinac Island in June 1885, but ornithologists only located small nestings in proceeding years.

Near the end of the century, brothers Stewart Edward and T. Gilbert White spent summers at their family’s Mackinac Island cottage. A prolific author, Stewart’s essay and list, Birds Observed on Mackinac Island, Michigan, During the Summers of 1889, 1890, and 1891, was published by the American Ornithologists Union. Of pigeons, he wrote, “A large flock was seen feeding in beech woods, August 30, 1889, after which they were frequently seen. About a hundred were observed September 10, and on September 12 the main body departed… None were observed in 1890 or 1891.”

On September 14, 1898, the last known passenger pigeon in Michigan was shot near Detroit. At the time, it was feared that other iconic animals, such as the bald eagle and American bison would follow this sad decline. The very last passenger pigeon in the world, “Martha,” died in her cage at the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914.

Today, it appears the extinction of this incredible species was not entirely in vain. Hard lessons learned helped fuel 20th century conservation efforts that brought some species back from the brink of disaster. During your next visit to the Straits of Mackinac, search the skies and you’re likely to find a bald eagle. As you watch it soar, remember the tale of the passenger pigeon, once a sign of spring in the north woods. No matter how common something seems, it’s up to us to care for all life to ensure the awe of future generations.