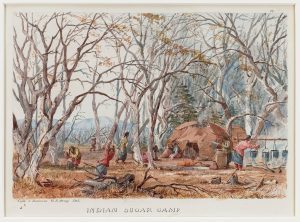

As winter snow and frigid temperatures finally give way to spring, maple sugaring season begins in northern Michigan. For many centuries, Native American families living at the Straits of Mackinac moved each spring from small winter hunting camps to groves of maple trees. There, they gathered and processed the first plant-based food of the year, harvesting maple sap and boiling it into sweet, calorie-rich maple sugar.

Early origins of maple sugaring are preserved in oral traditions of Anishinaabeg and other tribes of northeastern North America. When European missionaries and traders became established at Mackinac in the 18th century, local accounts of sugaring also began to appear in letters, journals, and other documents. Several such records offer a glimpse into historical methods and customs of sugar making in northern Michigan.

Sweet Science

No matter which specific methods are used, the basic science of converting maple sap into syrup or sugar remains the same. As temperatures rise above freezing during the day, liquid sap within trees thaws and starts to flow through sapwood. Sapwood is a living layer of wood within a tree which serves as a pipeline for moving water up to leaves so they can grow. The hard center of a tree, called heartwood, contains dead cells which provide rigidity but lack the ability to transport water.

While sap is mostly water, it’s not 100%. In trees, sugar maples contain the most sugar, from 2-4%. In a sense, trees plan ahead, as these complex carbohydrates were created last year, when green leaves converted sun’s energy into food through photosynthesis. Stored through winter, this energy flows to tips of branches in spring, stimulating buds to open. In late spring, when temperatures remain above freezing at night, pressure within a tree equalizes and sap stops flowing. If buds start to open, it also turns cloudy and tastes bitter.

While sap is mostly water, it’s not 100%. In trees, sugar maples contain the most sugar, from 2-4%. In a sense, trees plan ahead, as these complex carbohydrates were created last year, when green leaves converted sun’s energy into food through photosynthesis. Stored through winter, this energy flows to tips of branches in spring, stimulating buds to open. In late spring, when temperatures remain above freezing at night, pressure within a tree equalizes and sap stops flowing. If buds start to open, it also turns cloudy and tastes bitter.

When sap is freely flowing, a hole is made in a tree and a spout or spile inserted, directing drips into a waiting container. Traditionally, these containers were called mokuks, made of birch bark with sealed seams. When enough sap is gathered, it’s boiled over an open fire. Averaging about 2% sugar, sap must be boiled until it concentrates to 66% sugar in order to make syrup, with further boiling required for granular sugar. Generally, it takes 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup, which can make about 8 pounds of sugar.

Maple Sugar Making in 1763

Alexander Henry, a British trader at Fort Michilimackinac, was one of the first to describe the Anishinaabeg method of sugar making in Michigan’s north woods. He recorded the following as he recalled a visit to an Ojibwe encampment near Sault Ste. Marie in March 1763:

“The next day was employed in gathering the bark of white birch-trees, with which to make vessels to catch the wine or sap. The trees were now cut or tapped, and spouts or ducts introduced into the wound. The bark vessels were placed under the ducts; and, as they filled, the liquor was taken out in buckets, and conveyed into the reservoirs or vats of moose-skin, each vat containing a hundred gallons. From these, we supplied the boilers, of which we had twelve, of from twelve to twenty gallons each, with fires constantly under them, day and night. While the women collected the sap, boiled it, and completed the sugar, the men were not less busy in cutting wood, making fires, and in hunting and fishing, in part of our supply of food.

The earlier part of the spring it that best adapted to making maple-sugar. The sap runs only in the day; and it will not run, unless there has been a frost the night before. When, in the morning, there is a clear sun, and the night has left ice of the thickness of a dollar, the greatest quantity is produced.

Henry noted that work ended on April 25, resulting in 1,600 pounds of maple sugar, 36 gallons of gallons of syrup, and “…we certainly consumed three hundred weight. Though, as I have said, we hunted and fished, yet sugar was our principal food, during the whole month of April.” If his calculations are correct, this single camp collected about 16,640 gallons of maple sap. With an average of about 15 gallons of sap per tap, this would have required well over 1,000 taps to produce.

The Maple Sugar Trade

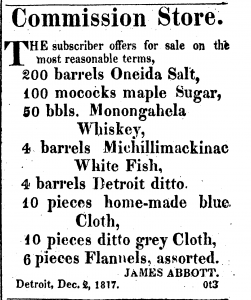

By the turn of the 19th century, maple sugar had become a regular item of trade at Mackinac, frequently appearing on manifests of trading vessels. In 1803, records from the U.S. Customs House on Mackinac Island included many dozens of kegs and mokuks of maple sugar transported by schooner and canoe. Traders such as George Schindler, Michael Dousman, Joseph Bailly, Jean Baptiste La Borde, Pierre Pyant, and many others appear time and again on such records. On July 19, 1810, for example, 489 “makaks” of sugar left Mackinac Island on the schooner Mary, bound for Detroit. There, advertisements for the newly arrived resource were published in newspapers, including the following example at the “Commission Store,” printed in issues of the Detroit Gazette throughout the winter of 1817-1818.

By the turn of the 19th century, maple sugar had become a regular item of trade at Mackinac, frequently appearing on manifests of trading vessels. In 1803, records from the U.S. Customs House on Mackinac Island included many dozens of kegs and mokuks of maple sugar transported by schooner and canoe. Traders such as George Schindler, Michael Dousman, Joseph Bailly, Jean Baptiste La Borde, Pierre Pyant, and many others appear time and again on such records. On July 19, 1810, for example, 489 “makaks” of sugar left Mackinac Island on the schooner Mary, bound for Detroit. There, advertisements for the newly arrived resource were published in newspapers, including the following example at the “Commission Store,” printed in issues of the Detroit Gazette throughout the winter of 1817-1818.

Bois Blanc Sugar Camp

A lengthy account of a maple sugar camp at the Straits of Mackinac was recorded by Elizabeth Therese (Fisher) Baird. Born in 1810, to parents of Scottish, French and Odawa ancestry, Elizabeth spent much of her youth on Mackinac Island. Fond childhood recollections of her family’s maple sugar camp were first published in the Green Bay Press-Gazette, on December 29, 1886. In part, she wrote,

“A visit to the sugar camp was a great treat to the young folks as well as to the old… All who were able, possessed a sugar camp. My grand-mother had a sugar camp on Bois Blanc Island, about five miles east of Mackinac.

About the first of March nearly half of the inhabitants of our town, as well as many from the garrison, would move to Bois Blanc to prepare for the work. Would that I could describe the lovely spot! Our camp was delightfully situated in the midst of a forest of maple, or a maple grove. One thousand or more trees claimed our care, and three men and two women were employed to do the work…

After describing methods and materials for making maple syrup, Elizabeth recalled the process of sugar making. In part, she described,

“The modus operandi thus: a very bright, brass kettle, was placed over a slow fire…containing about three gallons of syrup, if it was to be made into cakes; if… granulated sugar, two gallons of syrup were used. For the sugar cakes, a board of bass-wood about five or six inches wide, with moulds set in, in form of bears, diamonds, crosses, rabbits, turtles, spheres, etc. When the sugar was cooked to a certain degree it was poured into these moulds. For the granulated sugar, the stirring is continued for a longer time; this being done with a long paddle which looks like a mush stick. This sugar had to be put into the mokok while warm as it was not pack well if cold…”

Today, many Michiganders still enjoy the smell and taste of pure maple products each spring. Though methods have changed, we can all give thanks for trees which produce such sweet sap (with extra to spare), and for many generations of Native Americans whose skills in making maple products were passed down for thousands of years, ensuring we can still share these sweet gifts of the North Woods during this special time of year.