Since 1984, visitors to Historic Mill Creek have enjoyed demonstrations of Robert Campbell’s reconstructed sawmill, powered by water action from the swiftly running stream. Originally built about 1790, the Campbells also operated a grist mill (possibly attached to the sawmill) to grind grain into flour. In 1819, the entire operation was purchased by Mackinac Island entrepreneur Michael Dousman who ran the site for the next 20 years. Abandoned in 1839, the mills swiftly fell into ruin as nature reclaimed the property.

In 1860, William Myers retrieved the abandoned millstones from Mill Creek, hauling them about 13 miles to Cheboygan. There, he used them to produce flour for about five years before constructing a new mill in Grant Township, about six miles upstream from the city. Myers moved the old millstones to his new site, a picturesque grove “noted for years as one of the most romantic spots in this section.”

William and Catherine Myers had chosen a spot along a creek which came to bear their name, just upstream from the Black River. A German immigrant, Mr. Myers reportedly built his new machinery by hand, fitting the wheels with wooden pins in place of metal cogs. Described as “a regular Swiss mill in style,” the site served the community for nearly two decades. Tragically, the grist mill, along with the couple’s house and all its contents (including $250 cash), burned entirely on July 18, 1884. In spite of local fundraising efforts the mill was never rebuilt, and the stones lay abandoned, once again, on the bed of a shallow creek.

In 1892, an effort was made to retrieve the stones for display at the World’s Columbian Exposition, in Chicago. Rediscovered in Myers Creek by John Barclay, a local “land looker,” they were thought at the time to be the oldest millstones in “Michigan, or in the Northwest, being used hundreds of years ago to grind corn.” (Grist mills had actually been built at Detroit many decades earlier.) A description in The Cheboygan Democrat noted, “The stones are made from boulders found along the shores of the straits, and are about two feet in diameter, bound in iron, and are seemingly in good condition.”

Local lore recalls that farmer Walter Watson rafted the runner stone (top stone) down the river to his property, but it never made it to Chicago. For about 75 years, it served as the base for a burning barrel used by his family. The bedstone, partially broken, remained at the bottom of Myers Creek for many decades. It was recovered in the late 1960s and put on display at the Cheboygan Historical Museum. After being separated for more than a century, the set was finally reunited in the 1990s, when each was donated for display at Historic Mill Creek State Park.

“Lost Rocks” Explained

As noted above, Robert Campbell’s granite millstones were fashioned “from boulders found along the shores of the straits.” All over northern North America, stones and boulders of many types and sizes can be found scattered across the landscape. Called “lost rocks” or “hard-heads” by many settlers, they provided good material for locally-produced millstones, until higher quality stones were available.

Known today as “glacial erratics,” this material originated far to the north, scoured from bedrock many thousands of years ago by mountains of ice, as glaciers descended from modern-day Canada. Composed of granite, quartz, gneiss, and other ancient bedrock, most of these stones are much harder and older than native Mackinac limestone.

For many centuries, settlers and scientists had no idea how these seemingly bizarre boulders ended up here. In 1822, Henry R. Schoolcraft noted their presence on Mackinac Island, writing, “A locality of these abraded boulder-rocks, near the Dousman farm, is worthy of a visit from all who take an interest in the phenomena of boulders dispersed over the continent. The fishermen represent the water around this island to be eighty fathoms [480 feet] in depth. Yet, across these waters, to the upmost altitude of the island, these blocks of foreign rock have been transported. No force capable of effecting this is now known.”

The Theory of Continental Glaciation slowly became accepted after being introduced by Swiss professor Louis Agassiz in 1840. The professor stopped at Mackinac Island in 1848, bound for a geological expedition along the north shore of Lake Superior.

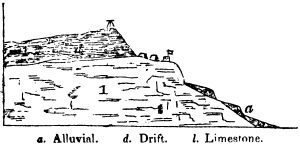

In 1851, a report for the United States Senate was issued by U.S. geologists by J.W. Foster and J.D. Whitney. Their cross-section of Mackinac Island illustrates a stratum of glacial drift 100 feet thick near the top of the island, under Fort Holmes. They note, “The boulders on the island, which are numerous, rest upon, or are imbedded in, the drift. From their external characters, it is inferred that they were derived from the northern shore of Lake Superior.”

As you walk the trails on Mackinac Island, at Historic Mill Creek, or in your own neighborhood, keep an eye out for these fascinating geological travelers. Much more than simple lawn ornaments, each rock has many stories to tell – of the ancient past, distant lands, and even our local history.