“A delightful drive the ice is very smooth this season, and there is just snow enough for good sleighing. The net poles for fish are so thick, that the Lake looks like a forest.” Amanda White Ferry, 1832

This winter, the Great Lakes have been nearly devoid of ice. Although floating masses filled portions of the straits, the larger lakes have been nearly ice-free. While mild winters weren’t unheard of in centuries’ past, Mackinac Island was often ice bound for six months at a time, nearly cut off from the outside world. Strong ice was counted on by local residents to obtain a critical winter harvest. For many generations, ice fishing provided an important source of food throughout the northern Great Lakes during cold winter months.

Long before European contact, Anishinaabek families at the straits were ice fishing experts, particularly for whitefish and lake trout. The tradition continued in Métis families, a culture of mixed French and American Indian ancestry. Spending the winter of 1767 at Fort Michilimackinac, Captain Johnathan Carver joined local residents in trout fishing through the ice. He described the process in detail, noting three or four hooks affixed to strong lines often caught two trout at a time, frequently weighing up to forty pounds each. Preserving them in cold months was accomplished simply by hanging them outdoors, where they froze solid in one night.

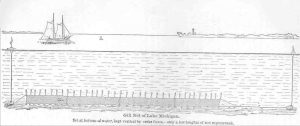

Although they’re smaller (weighing about four pounds) lake whitefish have long been described as notably more delicious. Generations of writers raved about their delicate flavor and seemingly endless abundance. Whitefish live at deeper depths than trout and have small mouths, so they were typically caught with gill nets sunk beneath the ice.

Amanda White Ferry, wife of missionary Rev. William Ferry, lived on Mackinac Island from 1824–1834. Her correspondence included many references about ice conditions, winter fishing, cutting ice, sleighing, and dog sledding. On January 8, 1824, she wrote, “The weather is remarkably mild so that the Lake is still open … Recently, many who had had been entirely out of provisions, set their nets upon a small patch of ice, surrounded by water. In the night a wind arose, carried off the nets ice and all (eleven in number); they have no method of making more.”

When good ice was present, fishing was pursued vigorously. Mrs. Ferry described the process in late February 1831, writing, “We went onto the ice and saw the manner of setting the nets for fish. Two holes, several rods distant from each other are cut in the ice. By each of them a stake is driven and a cord is strung with nets, weighted to fall, and attached to the stakes. The fish in passing with the current are caught in the nets, and whoever has tasted of Mackinac White Fish knows how delicate and delicious they are. As we glided over the ice on the bay, we could see clearly through its clearness stones on the bottom as plainly as though they lay on the surface.”

Amanda’s sister, Hannah White, spent the entire winter of 1831-32 on Mackinac Island, visiting from Massachusetts. On March 12, a letter to her parents described a morning adventure to witness a net being taken up. “As we rode along,” she wrote, “we could see through the clear ice all that lay upon the bottom of the Lake, even when the ice was two feet thick. When there is no snow, fisherman can frequently see through the ice what their nets contain.” Sometimes, net poles were so numerous it appeared as if a forest had sprung up on the icy Straits of Mackinac.

Such dramatic scenes have long since faded beyond the memories of Mackinac’s oldest inhabitants. If a forest appears on the lake today, it’s likely a row of Christmas trees marking the elusive “ice bridge” for snowmobiles to follow between St. Ignace and Mackinac Island. Someday, this too may become a forgotten tradition. In recent decades, unpredictable winter weather has caused warmer lakes and more thawing, promising an uncertain future for winter forests on the ice.