On June 19, 1865, General Gordon Granger, accompanied by 2,000 federal troops, read out General Order No. 3 to the residents of Galveston, Texas. Gordon and his troops were part of the federal forces occupying the defeated states of the defunct Confederacy. The order informed the people of Texas that all formerly enslaved African Americans were free, and although American slavery would not be completely abolished until the ratification of the 13th Amendment on December 18, 1865, June 19th is now celebrated as Juneteenth, marking a significant episode in the defeat of slavery in the United States.

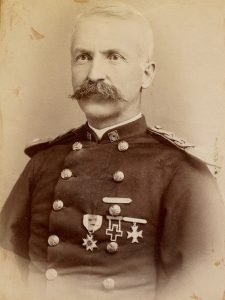

While General Granger was reading General Order No. 3, two future Fort Mackinac officers were also on occupation duty in the south. William Manning and future post commander Greenleaf Goodale were both stationed in Louisiana in the summer of 1865. Goodale served as a captain with the 77th Infantry, U.S. Colored Troops, while Manning acted as major to the 103rd Infantry, U.S. Colored Troops. Both units were comprised of African American enlisted men, some of them formerly enslaved. Manning had served alongside African American soldiers since 1863, when he accepted a lieutenant’s post with the 35th Infantry, U.S. Colored Troops. The regiment saw heavy fighting at the Battle of Olustee in Florida in 1864. During a fierce rearguard action, the soldiers of the 35th, along with African American members of the well-known 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, helped repel Confederate cavalry attacks. Manning was severely wounded in the battle, and transferred to the 103rd Regiment.

By the time Goodale and Manning served at Fort Mackinac with the 23rd Infantry in the 1880s, the U.S. Army had shrunk considerably, with far fewer units than had existed during the war. African American soldiers were still forced to serve in segregated regiments with white officers. None of these segregated units, the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments and the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments, served at Fort Mackinac. However, Goodale and Manning both carried the experiences they gained (and for Manning, the wounds he sustained) serving alongside African American troops during the war for the rest of their careers. The American military remained officially segregated, with African American officers and soldiers serving in separate units, until 1948.

Today, as Juneteenth celebrations mark a victory over the system of American enslavement, we hope that you’ll reflect on the legacies of slavery and the service of African Americans during the Civil War. If you would like to learn more about Goodale, Manning, and their experiences during the war, two of Mackinac State Historic Parks’ recent publications, The Soldier’s of Fort Mackinac: An Illustrated History and Through an Officer’s Eyes: The Photo Album of Edward B. Pratt, U.S. Army 1873-1902 discuss these and many other officers’ careers. Fort Mackinac has officially opened for the season, so we hope that you will join us soon to hear more about how the Civil War shaped the lives of the men of the 23rd Infantry in the 1880s.