On July 18, 1815, Mackinac Island once again became part of the United States after three years of British occupation during the War of 1812. The war brought many changes to the island, including the construction of a second fort on the heights of Mackinac. This weekend, this small post, Fort Holmes, will come to life to tell the story of Mackinac Island during the early years of peace.

The Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war, stipulated that all territory captured by either belligerent be returned to its former owner. Colonel Anthony Butler and a large contingent of American troops accordingly arrived on the island on July 18, 1815, and within 30 minutes took possession from British commander Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDouall. Butler soon returned to Detroit, leaving Lieutenant Colonel Talbot Chambers in command.

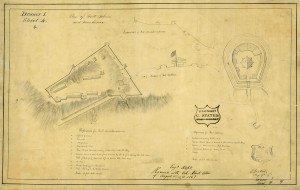

By at least early September, the Americans had renamed Fort George, a small fort built by the British on the island’s highest point. The small post above Fort Mackinac became Fort Holmes, in memory of Major Andrew Holmes, killed in the 1814 Battle of Mackinac Island. The horseshoe-shaped fort was surrounded by a defensive ditch, and its earthen walls were topped with a fraise, a row of sharpened, horizontal logs. Inside the fort Chambers found a “tolerable strong” two story blockhouse capable of mounting two 12-pound cannons, as well as unfinished gun platforms for 11 artillery pieces. In addition to two bombproof shelters just outside the gate, Chambers found an advanced battery for two 24-pound guns overlooking Fort Mackinac and the harbor below. “This work we shall render strong as possible,” vowed Chambers, who instructed his men to complete the gun platforms and arm Fort Holmes with two brass 12-pound guns, two howitzers, a long 24-pound gun, and two 6-pound guns placed to rake the defensive ditch. The soldiers stored ammunition in one of the underground bombproofs, using the other to hold food and other provisions. Chambers quickly incorporated Fort Holmes into his defensive scheme for the island, making it the primary American redoubt in the event of an attack. With Fort Holmes thus armed and manned, Chambers boasted that he “would not fear the best two thousand troops that Britain can send against us, even were they to be headed by a Wellington.”

In contrast to his appreciation of Fort Holmes’ defensive potential, Chambers had nothing but scorn for Fort Mackinac’s military usefulness. Although Chambers estimated that the larger fort could accommodate 300 men, and had an ample powder magazine and numerous workshops, he placed little value in the post as a fighting position: “Were we solely dependent on the resistance which fort Mackinaw would be enabled to make, our situation would indeed be deplorable.” He believed that only Fort Holmes could properly defend the island, and thus issued orders requiring almost every soldier to repair to the hilltop post in an emergency. Despite Chambers’ high opinion of Fort Holmes, America troops garrisoned the fort only during the summer months, and the small post was abandoned and allowed to decay at the end of 1817.

In contrast to his appreciation of Fort Holmes’ defensive potential, Chambers had nothing but scorn for Fort Mackinac’s military usefulness. Although Chambers estimated that the larger fort could accommodate 300 men, and had an ample powder magazine and numerous workshops, he placed little value in the post as a fighting position: “Were we solely dependent on the resistance which fort Mackinaw would be enabled to make, our situation would indeed be deplorable.” He believed that only Fort Holmes could properly defend the island, and thus issued orders requiring almost every soldier to repair to the hilltop post in an emergency. Despite Chambers’ high opinion of Fort Holmes, America troops garrisoned the fort only during the summer months, and the small post was abandoned and allowed to decay at the end of 1817.

Today, a reconstructed Fort Holmes once again stands on Mackinac Island’s highest point. This weekend, June 24-25, living historians from around the Great Lakes will garrison the fort and tell the story of the American soldiers who guarded Mackinac Island immediately after the War of 1812. In addition to historical interpreters from Mackinac State Historic Parks, volunteers from the 7th United States Infantry Living History Association and Gower’s Company of the 1st Regiment of Riflemen will post guards, perform firing demonstrations, and lead tours of Fort Holmes. This event is free, and will take place from 10:00 AM to 5:30 PM at Fort Holmes.